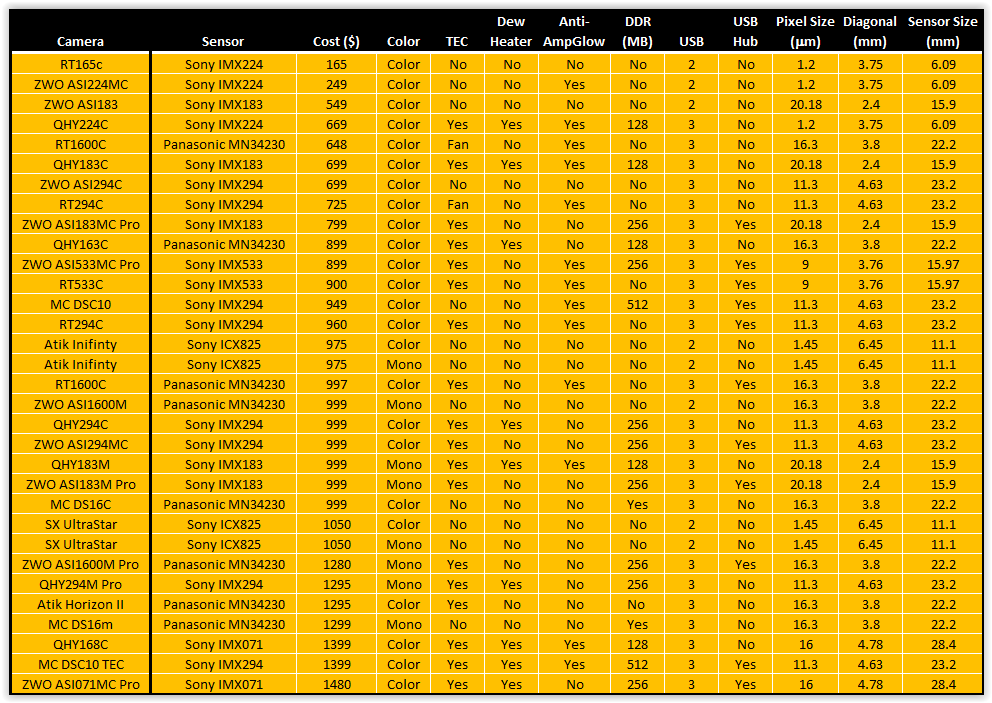

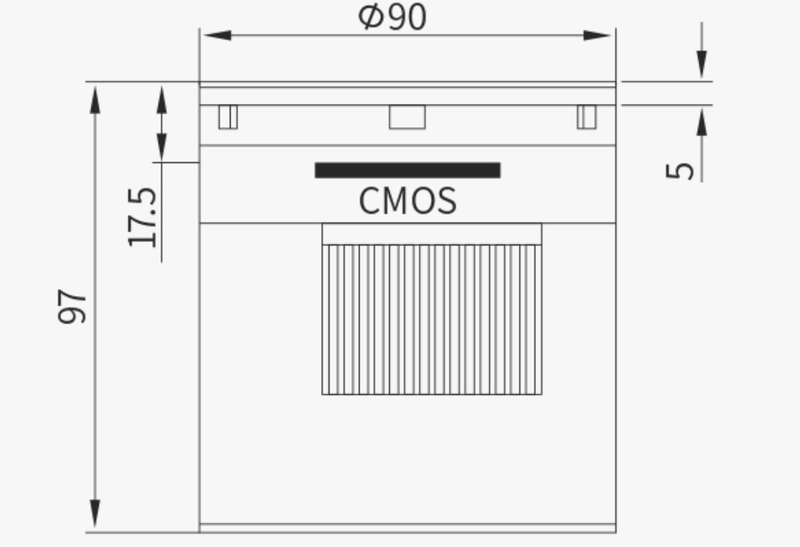

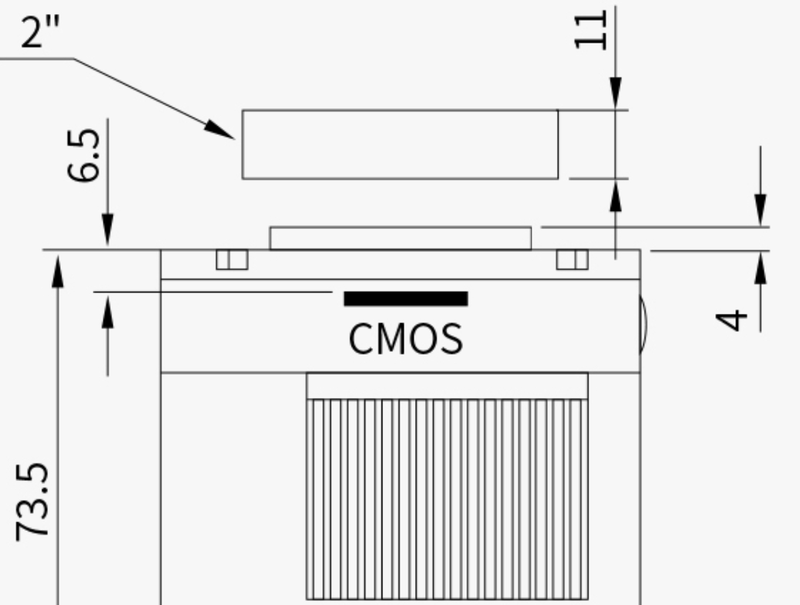

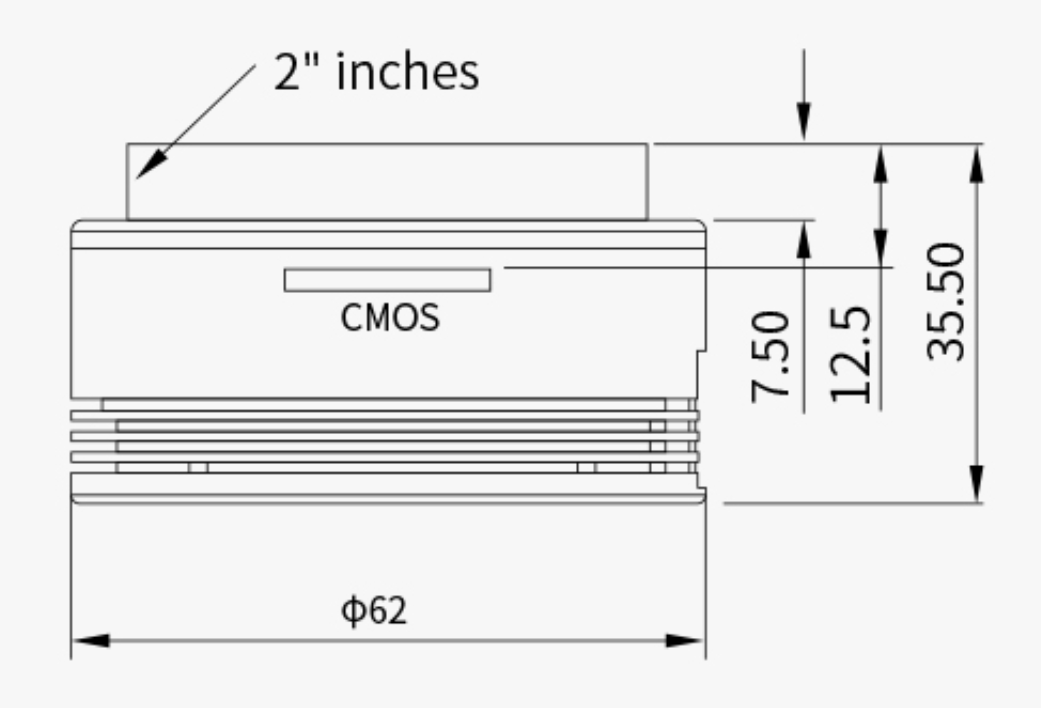

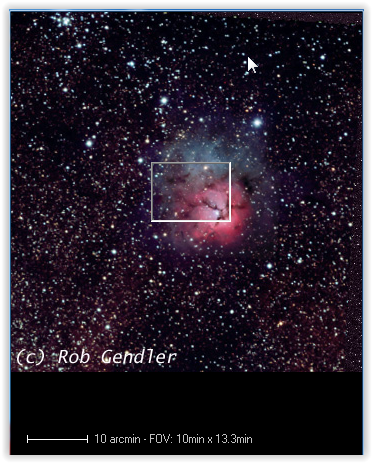

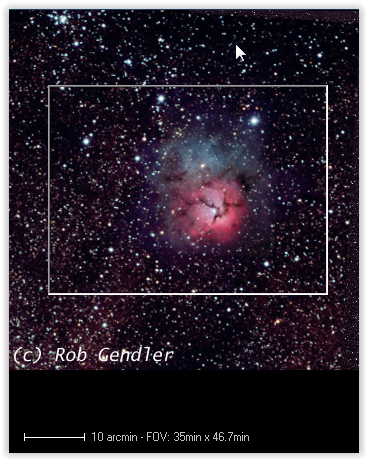

Celestron's 6.3X focal reducer/field flattener is a very popular accessory for non-Edge SCTs because it reduces the focal ratio of the SCT from its native f/10 to f/6.3. This increases the field of view (FOV) and increases the optical speed of the SCT as well. Both effects are helpful for astrophotography and Electronically Assisted Astronomy as they make shorter exposures possible and allow larger Deep Sky Objects (DSOs) to fit in the camera's sensor. And because it is also a field flattener it will improve the sharpness of the image at the edge of the FOV. The same benefits of a wider field and more intense image apply to visual observers as well Reducing the focal ratio with this reducer speeds up the optics by a factor of (10/6.3)^2 = 2.5. It concomitantly increases the FOV by the same amount. For instance, an 8" SCT with the ZWO ASI533MC camera has a FOV of 19.4 x 19.4 arcminutes at f/10 which increases to 30.8 x 30.8 arcminutes at f/6.3. That is 376 arcminutes-squared vs 949 arcminutes-squared with the later 2.5X the former. For the 8" SCT the focal length reduces from 2000mm to 1260mm with the reducer. Determining the Correct Back Spacing Target For any focal reducer to work as designed It is important to place the sensor of the camera at the correct back spacing, or distance, from the focal reducer. This will ensure that the focal reduction will match the design target, in this case 6.3X. It also ensures that the field flattener works optimally to provide sharp, round stars to the edge of the FOV. If the camera's sensor is placed closer to the focal ratio will be larger, say 6.5X or 7X, and the focal reduction will be less. If it is placed further from the reducer the focal ratio will be smaller, say 6X or 5X, and the reduction will be more. In addition, the field flattener will not perform optimally so stars near the edge of the FOV may be distorted. For astrophotography we want to get the best possible images so we want to be as close to the ideal back spacing as possible. For Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) we may be less fussy about the edge of the FOV and more interested in speeding up the optical system and/or fitting more of the larger DSOs in the FOV. In that case a slightly larger back spacing is sometimes used. Regardless, it is important to know how to get the correct back spacing to begin with.  Different locations often identified as the back spacing measurement starting point. 1) Center of the internal lens'; 2) Inner flange; 3) Outer edge of the threads; 4) Back flange. Different locations often identified as the back spacing measurement starting point. 1) Center of the internal lens'; 2) Inner flange; 3) Outer edge of the threads; 4) Back flange. So, how do we achieve the correct back spacing when using the Celestron 6.3X focal reducer? We need to know the correct back spacing and how it is measured. If you search the internet you will find answers ranging from approximately 100mm to 110mm with the most common answer being 105mm. Surprisingly Celestron has not published a spec for the back spacing for this reducer. If you also look to find out where on the focal reducer the back spacing measurement is made, this is where you will find the most disagreement. Some suggest the measurement should be made from the center of the lens' inside the focal reducer (1 in the image above), others from the flat surface on the inside of the threads (2), or the back edge of the threads (3) as shown in the photo. The correct answer to both of these questions is 105mm from the extreme back surface of the focal reducer as shown in the photo identified as location 4 in red. So how do we know that these are correct?  Celestron SCT T-Adapter (50mm) Celestron SCT T-Adapter (50mm) First, we know that the industry standard back spacing for focal reducers used on refractors is 55mm (there are some exceptions). Second, because the optics of an SCT is very different from a refractor it is not possible to make a focal reducer for an SCT with a back spacing of 55mm. So, Celestron did the next best thing. They made an adapter which attaches to the back of the focal reducer and is exactly 50mm long. This leaves the industry standard 55mm left to obtain the correct back spacing of 105mm. Also note that the 50mm length of this adapter is measured from the the flat surface of the flange which mates with the surface "4" in the image above to the flat surface on the other end of the adapter not including the threads where the next spacer will bottom out when screwed all the way on. Similarly, Celestron makes a 7X focal reducer for their Edge SCTs and in this case they do specify the back spacing as 146.05mm. And likewise, they make a T-Adapter to attach directly to this focal reducer which is 91mm long leaving 55.05mm of additional spacing to meet the back spacing spec. So, I think it is clear that the design back spacing for the 6.3X reducer is 105mm and not 100mm, 110mm or something else, and that it is measured from surface 4 on the focal reducer. Imaging Train Options for the 105mm Back Spacing Now that we have established that we need 105mm of spacing for the Celestron 6.3X reducer we need to figure out what options are readily available. But first, we need to take into account the back spacing of the camera sensor itself. This can be found from the manufacturer and we will use ZWO's ASI cameras as an example. Below is ZWO's mechanical drawing for their ASI2600MC camera. This shows the position of the CMOS image sensor relative to the front surface of the camera to be 17.5mm. Likewise the ASI585MC has a back spacing of 17.5mm for the sensor even though it uses a different coupler on the front face. If you look at most cameras these days from ZWO and other manufacturers you will find that 17.5mm is the most common back spacing for the sensor. However, be careful to check as the ASI224MC shown below only has a 12.5mm back spacing. Like plumbing or garden irrigation systems there are many different spacers and adapters available such that one can find many combinations of such to make up the additional back spacing needed. After searching through multiple astronomy supplier's sites I have come up with what I believe to the be the least complicated solutions using the simplest set of adapters available to achieve the 105mm back spacing. I list the parts needed below along with links to either Agena Astro or HighPoint Scientific, two of my goto astronomy suppliers. Links are affiliate links which will earn a small commission at no cost to you. Please use these if you can to support my web site. From Agena Astro Celestron 6.3X focal reducer Celestron 50mm SCT-T Adapter Blue Fireball 37.5mm Extension ZWO 11mm Female to Female Adapter If you want to fine tune the spacing you can use Baader T2 Delrin spacers to adjust the spacing in small increments from 0.6 to 1.4mm. If you want to make larger spacing changes you can search for the desired M42/T2 spacer from Blue Fireball, or substitute the Baader Varilock 46 T2 Variable Extension in place the 37.5mm Extension listed above for greater versatility. Here is an almost identical solution from HighPoint Scientific. Since they do not list a 37.5mm spacer it uses a 30mm and 7.5mm spacer which are sold together as a kit from Celestron. From HighPoint Scientific Celestron 6.3X focal reducer Celestron 50mm SCT-T Adapter Celestron M42 Spacer Kit (30mm + 7.5mm) ZWO M42 Female to Female 11mm Adapter Alternatively to the Celestron M42 spacer kit one could substitute the Baader Varilock 46 T2 Variable Extension which, while almost twice as expensive, allows for variability in the spacing. Also the Baader T2 Delrin Spacer Ring Set is an option for fine tuning the spacing on the order of a mm or less. Back Spacing Solutions With a Filter Drawer Now if we want to use filters with our camera we can put a filter drawer in line so that it is easy to change filters in real time. In this case we will need some different spacers and adapters. Also, we need to take into account the fact that the glass of the filter has a different index of refraction compared to air. Filter glass is typically 2-3mm thick so we need to add ~1/3 of that thickness to our optical path for an additional ~1mm. Below is the same setup as above showing the parts needed along with links to either Agena Astro or HighPoint Scientific. Agena Astro Celestron 6.3X focal reducer Celestron SCT-T Adapter Blue Fireball 10mm Extension Blue Fireball 7.5mm Spacer Ring ZWO M42 11mm Female to Female Adapter ZWO Filter Drawer M42 Male to M48 Female ZWO M48 Male to M42 Female Adapter HighPoint Scientific Celestron 6.3X focal reducer Celestron SCT-T Adapter Apertura10mm Extension Baader 7.5mm T-2 Extension ZWO M42 11mm Female to Female Adapter ZWO Filter Drawer M42 Male to M48 Female ZWO M48 Male to M42 Female Adapter Back Spacing Solutions for SE/Evo/CPC Mounts at 90deg Altitude The solutions above work with cooled and uncooled cameras on any Equatorial mount. In the case of a single arm Alt-Az mount like the Celestron SE or Evolution mounts, or a dual arm mount like the CPC mount, the solutions above will only work as long as the OTA is not pointed higher than ~75 degrees in altitude. Higher altitudes will cause the camera to crash into the base of the mount. A simple solution to reach an altitude of 90degrees without hitting the mount is to add a rail extension along with the imaging trains shown above so that the OTA can be pushed forward to provide enough additional clearance. An inexpensive rail extension is available from SVBony which will work on the 6" SCT. The longer Celestron Universal Mounting Plate is probably a better option for the 8" and 9.25" SCTs and is available from both Agena Astro and HighPoint Scientific. If using a cooled camera there will not be enough room to push the OTA forward and a different approach is needed. This approach uses a diagonal to place the camera at a right angle to the optical axis to gain additional clearance. The details of this configuration can be found in the equipment recommendations section of this web site here. If you would like to see all of these configurations in action, please take a look at the video I put together on this subject where I demonstrate each solution in detail. The video is on my YouTube channel here where you can also find other helpful videos for the amateur astronomer. All links are affiliate links which can earn a commission without any additional cost to you. Please consider using them to help support this channel.

0 Comments

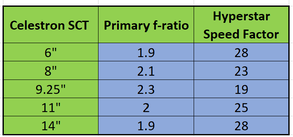

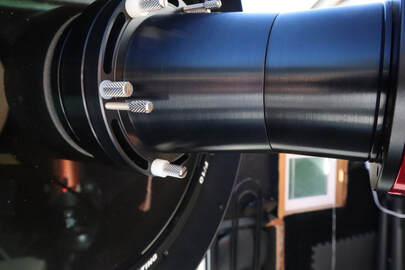

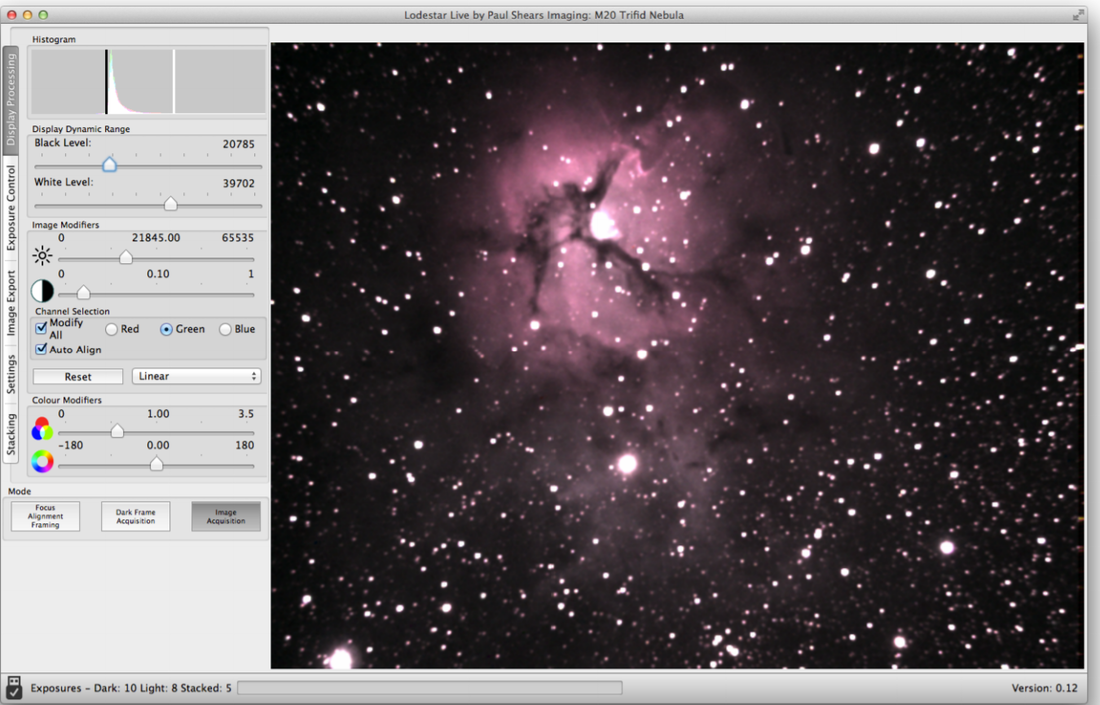

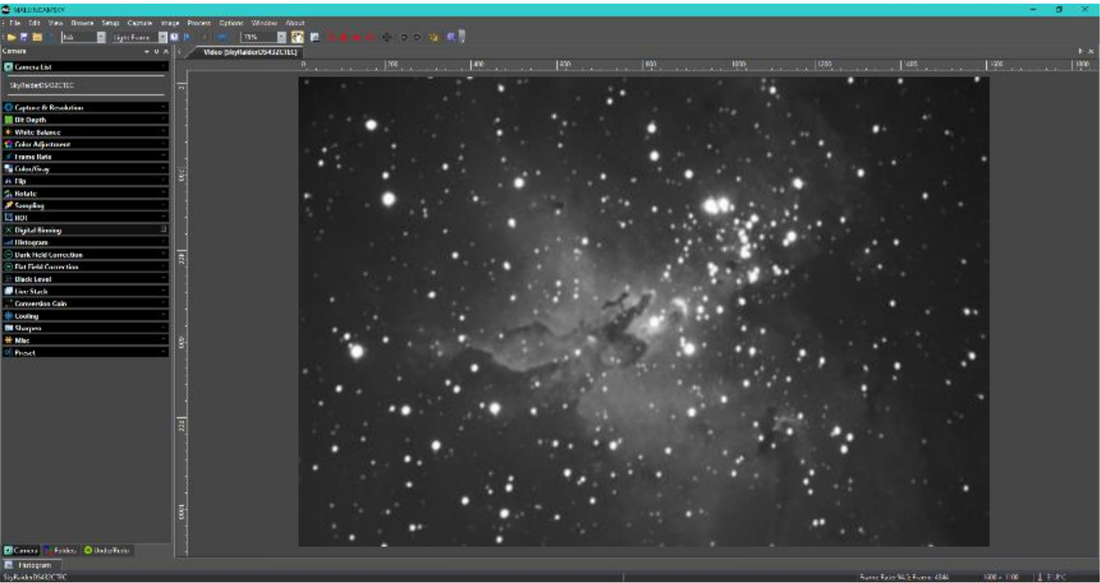

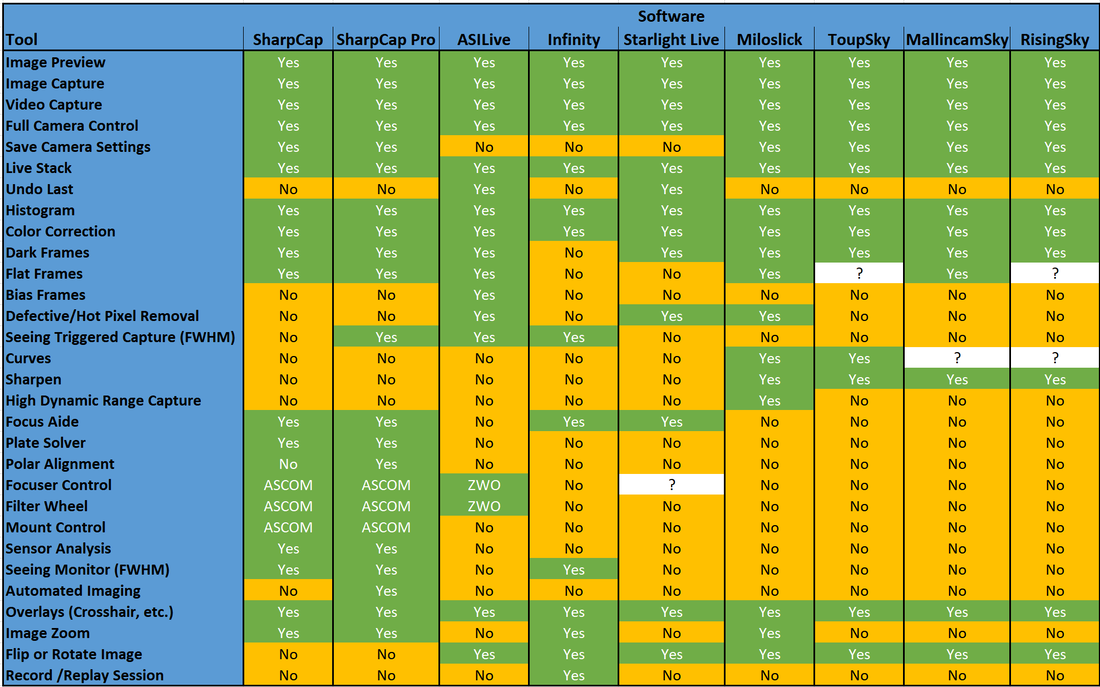

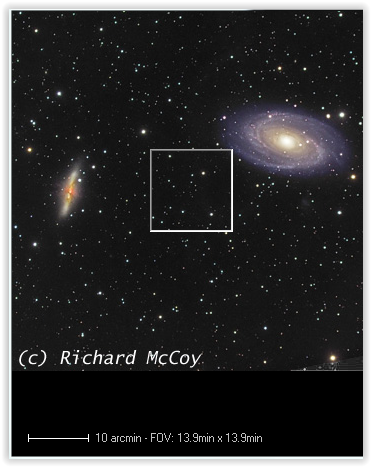

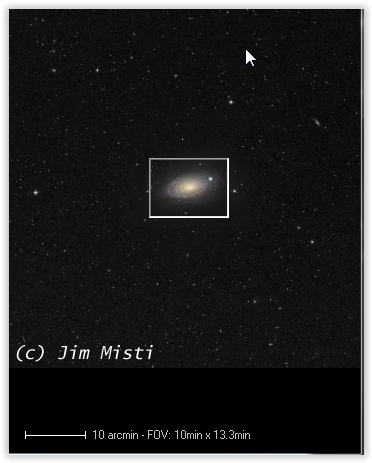

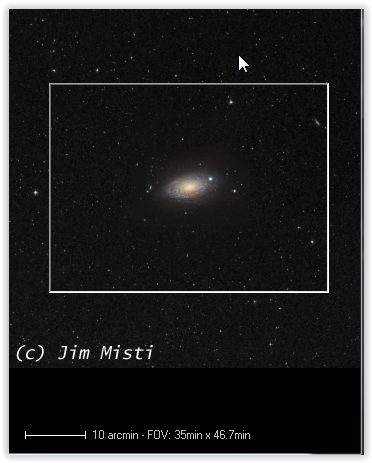

22 sec image of NGC253 Hyperstar on a 14" SCT 22 sec image of NGC253 Hyperstar on a 14" SCT If you own a Celestron SCT and do not already have a hyperstar adapter you should. What is hyperstar? It is a multi-element optical adapter which converts the focal ratio of an SCT from its native f/10 to f/2. Since the optical speed of a telescope is proportional to the square of its f-ratio, adding a hyperstar will increase the speed of an SCT by a factor of 25: speed ~ (10/2)^2 = 5^2 = 25. My first experience with hyperstar was back in 2015 when I first tried it on my 14" SCT to capture a breathtaking view of NGC253 the Sculptor Galaxy in just 22seconds. I was just blown away by what the hyperstar was able to capture in such a short time. Of course, smaller aperture telescopes will not produce such an image in the same time, but they will still have 25X faster optics resulting in amazing images in short times of their own right. Hyperstar is available for the 6", 8", 11" and 14" Celestron Edge and non-Edge SCTs and the 9.25" Edge version. It has been available for these models for some time. Just check the front of the Secondary mirror for the phrase "Fastar", where Fastar is the original Celestron name for this, to see if your older model is compatible. For those that do not say "Fastar" a conversion kit is available for all 6" through 14" models except the 9.25" model.  How does hyperstar work? An SCT consists of three optical elements, a corrector plate at the front, the primary mirror in the back and the secondary mirror in the center of the corrector. SCT primaries are spherical mirrors configured to a focal ratio of f/2. Actually the focal ratio of a Celestron SCT primary varies between f/1.9 and f/2.3 depending upon the model as shown in the accompanying table. For the sake of simplicity, lets stick with f/2 as our example. The secondary mirror is figured to a focal ratio of f/5 so the combined effect is a focal ratio of f/10, f/2 x f/5 = f/10.  The camera adapter is seen between the hyperstar and the camera. The camera adapter is seen between the hyperstar and the camera. Hyperstar is installed by removing the secondary mirror and replacing it with the hyperstar compound lens. With no secondary the focal ratio is that of the primary mirror, or f/2. Obviously the hyperstar element can only be used with a camera for imaging, either for traditional astrophotography or electronically assisted astronomy, and not for visual observations. A camera is attached to the hyperstar via an adapter which is specific to the camera and hyperstar size. The light enters the SCT through the front corrector plate and reflects off the primary mirror just as it always does. But now, instead of reflecting off the secondary mirror back through the center of the primary and out the back of the SCT, it travels through the optical elements of the hyperstar and into the camera. The hyperstar is a multi-element lens/corrector which not only focuses the light onto the sensor in the camera, but also corrects for the spherical aberrations and field curvature which would be present without the corrective capability of the hyperstar. Images taken with the hyperstar should be sharp and flat across the field of view. Hyperstar can be used for both traditional astrophotography and electronically assisted astronomy. In both cases, the faster focal ratio enables more light to be collected in a given time compared to the SCT's native focal ratio of f/10. The results can be stunning as in the traditional astro photo of M31 shown below taken on a C11 with hyperstar for a total exposure time of 213 minutes using Pixinsight to combine and process hundreds of sub-frames. Similarly, amazing results can be obtained during live stacking and viewing during an EAA session as seen in the image of the Rosette Nebula taken with TSX's Live Stack feature stacking and stretching 120 x 5 sec sub-frames for a total of 10 minutes also using a C11 with hyperstar.  A C11 with hyperstar and an ASI2600MC A C11 with hyperstar and an ASI2600MC Installing Hyperstar Removing the secondary mirror from your SCT may sound scary but it really is a simple matter. I like to set the OTA at a slightly elevated angle so it is easy to reach the secondary and gravity will still help to keep it in place when its retaining ring is removed. The secondary slides out and can be placed into the protective holder which comes with the hyperstar. The hyperstar is threaded onto the secondary holder. But be careful not to over tighten the hyperstar. Finger tight is sufficient. I once got the hyperstar so tight that I had to remove the corrector plate to get it back off. You should not have this problem if you do not over tighten the hyperstar like I once did. After installing the hyperstar several times you will even feel comfortable doing this in the dark. The procedure should take only 5min or less. While hyperstar can weight as much as 3lbs for the 14" SCT it is not going to damage your corrector plate when handled carefully. An SCT corrector plate is much stronger than one may realize. Still, I would never transport an SCT with a hyperstar installed as the possibility of banging into the hyperstar is always present. Also, when covering the telescope using a hyperstar with an all weather cover just be careful that the cover does not snag on the hyperstar which protrudes from the OTA. I leave my hyperstar on for multiple days while in the field using a dew shield and cover over the hyperstar and correct which keeps dirt and dust off the corrector. At home I leave my hyperstar mounted on my SCT in the backyard observatory as long as I plan to work at f/2. There is really no need to remove and re-install hyperstar every day.  Push/Pull collimation pins at left and a rotation thumbscrew at bottom Push/Pull collimation pins at left and a rotation thumbscrew at bottom Hyperstar Collimation Just like the secondary mirror on an SCT, hyperstar will need to be collimated from time to time. Fortunately, hyperstar seems to hold collimation just as well as a secondary mirror so you should not expect to need to collimate any more frequently than you do without it. Also, you most likely will not need to re-collimate your scope when you put the secondary back since it is indexed to the optical axis with a pin which fits into a notch in the flange which holds the secondary. Hyperstar has 3 sets of push/pull pins located at 120 deg increments around the outside for the purpose of collimation. There are two strategies for initial collimation. The simplest takes advantage of the high precession machining of the two hyperstar mechanical bodies. Just adjust the push/pull pins so that both flanges of the hyperstar bodies are in contact all the way around and then tighten the pins. So long as these two flanges are parallel to one another and the corrector plate is aligned with the primary mirror you should have good collimation. Several folks have reported that this has worked for them so it is worth trying first. If you are not satisfied with the collimation with that approach you can use the second method. With this approach you will need 3 shims 30 to 40 mil thick. Metal stock of this type can be found at your local Ace hardware or online. I use Cu stock which I cut into 3 pieces long enough to fit between the two hyperstar flanges. With the shims spaced 120 degrees apart between the two hyperstar flanges, tighten the push/pull pins just enough so that you can barely pull the shims out. Make sure that you tighten pins are engaged so that the flanges do not come loose. Then, under the stars perform a collimation as you normally would using the push/pull pins in the same way as you would the 3 screws on the back of the secondary mirror. You will find that it is a lot easier to adjust the push/pull pins with your fingers. Just make sure they are all tight when you are satisfied with collimation. A very large variety of cameras are compatible with hyperstar including those from ZWO, QHY, ATIK, SBIG, etc. When ordering the hyperstar element you will need to specify the camera that you will use with it since a camera adapter is required to attach the camera to the hyperstar lens at the optimum distance from the camera sensor.  Hyperstar filter drawer and slider Hyperstar filter drawer and slider Using Hyperstar The hyperstar adapter has 3 thumbscrews which are designed to allow 360 degree rotation of the hyperstar so that you can adjust the orientation of your camera. Just loosen all three thumbscrews 1/4 turn, rotate the the outer body of the hyperstar to the desired orientation of the camera. Then tighten the thumbscrews to lock the camera orientation. Since these thumbscrews hold the two halves of the hyperstar together, you should never completely remove them. USB and power (if needed) cables are attached to the camera as usual. If you are using a dew shield you can either bring the cables out the front of the shield or, out the back of the shield if it has a notch in it. In either case tie off the cables so they do not drag. In some cases, the cables may produce diffraction spikes on bright stars just like the spider vanes on a Newtonian secondary. This can be minimized by avoiding running the cables in a straight line across the front of the OTA. The hyperstar camera adapter is threaded inside so that a filter can be attached. This works well if you intend to use only a single filter, such as a light pollution filter, a UV-IR filter or a multi-band filter during you imaging session. Just unscrew the front piece on the adapter, screw in the filter and screw the adapter/filter combination back on. Then attach the camera. If you want to change filters during a session you will need a filter drawer for the hyperstar. The filter drawer screws onto a separate hyperstar adapter such that the combination provides the correct backspacing for your camera. Everything else in an imaging or EAA session will be the same as if you did not have the hyperstar except it will require much less time to be able to see DSOs compared to operating at f/10. Wide Field Since the hyperstar reduces the focal ratio to f/2 but does not reduce the aperture of the telescope, the field of view will be much wider. In fact, the field of view will also be 25X larger compared to f/10, 5X in each axis of the camera sensor. This is precisely how the hyperstar speeds up imaging. To understand this let's take a look at the difference in image scales at f/10 and f/2. Image scale depends upon the size of the pixels in the camera and the focal length of the telescope. It is defined by the following equation: Image Scale (arc-sec/pixel) = 205 x pixel size (microns) / focal length (mm) So, for the same camera, the image scale varies inversely with the focal length. In other words, the image scale increases as the focal length gets smaller. Adding the hyperstar reduces the focal length proportional to the reduction in focal ratio. For the C11 discussed above the focal length is reduced from its native 2794mm to 559mm with hyperstar. The image scale is then reduced by the same factor of 5 across the x and y axis of the camera chip. This means that each pixel is collecting light from an area of the sky 25X larger with the hyperstar than without the hyperstar which is why the exposure time is reduced. Keep in mind that with the wider field of view the resolution is now reduced by the same amount. But since seeing conditions usually dominate image resolution stars and most CMOS cameras used for astronomy have sensors with pixels smaller than 4microns on a side the image quality will still be excellent, even if you zoom in on the image. Summary

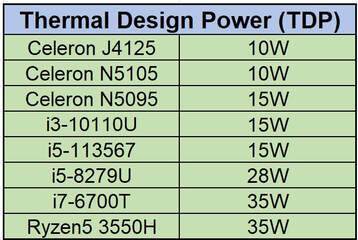

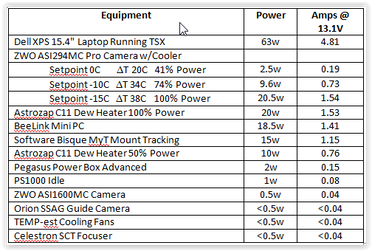

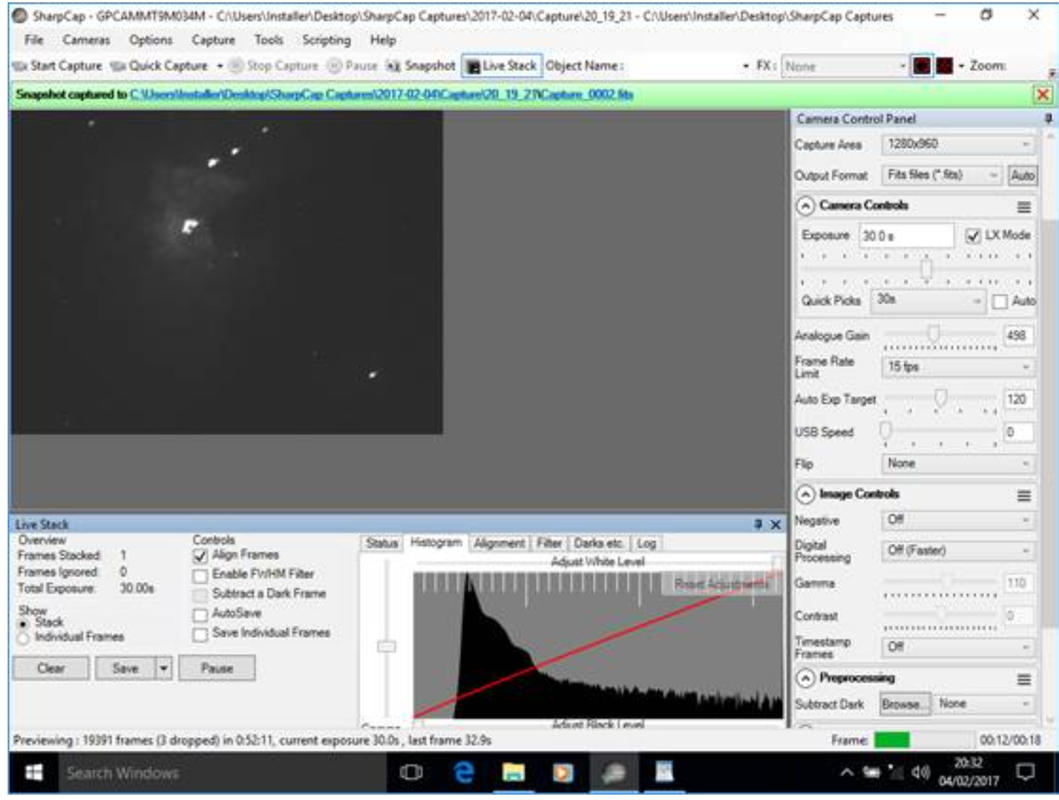

Hyperstar is certainly expensive costing just under $1000 for an 8" SCT and more for larger apertures. However it should be viewed as turning your f/10 SCT into a completely new telescope with a focal ratio at least 4X faster than the fastest refractors available while maintaining an aperture many times larger than a refractor. Think of it as investing in an entirely new scope but without having to purchase a new set of accessories (finder, dew heater, focuser, etc.). As the few images shared here show, hyperstar can produce incredible images in real time and is well suited to capturing more of the larger DSOs. If you want to see more about the amazing hyperstar check out my hyperstar YouTube video Links are affiliate links which can earn a commission without any cost to you. Please consider using them to help support this web site. Hyperstar is available from HighPoint Scientific bit.ly/3RO8vgv  Mini-pcs are becoming increasingly popular for both Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) and astrophotography. This is because a mini-pc allows one to connect remotely to the telescope, mount, camera, and other equipment with a laptop, tablet or phone without being tethered by a USB cable. Remote may mean inside one's house while the telescope is out in the back yard or inside a small tent or EzUp where you can stay comfortably warm and away from annoying bugs when observing away from home. It may even mean sitting in your own house with your telescope set up at a distant remote observatory. In my case, it means being inside my house when observing at home with my equipment setup in the backyard observatory or inside my RV when at a star party or other remote site. Being untethered allows me to move freely from inside (house or RV) to the side of the telescope whenever I need to be close but then being able to return to the inside for most of the night. Utilizing a mini-pc at the telescope will also reduce the power required to keep everything running through the night. A mini-pc uses much less power than a typical laptop. If you connect remotely to the mini-pc with a laptop you can still save power since you do not have to have the laptop on all the time since it is only being used as a monitor to check in on the mini-pc from time to time. In fact, you can simply turn off the laptop once the mini-pc is up and running and leave it off until you are ready to shut down the session. A tablet or phone can be used instead of the laptop to remote into the mini-pc which gives more options in terms of saving power since these use much less power than a laptop. What is a Mini-PC? A mini-pc is a headless computer which comes in a small form factor typically 5" - 6" on a side by about 2" - 3" thick or even smaller. Headless means that it comes without a monitor, keyboard or mouse. This cuts down on the size, cost and power consumption, all important for astronomy applications. Since a mini-pc is a computer it will have a CPU, RAM, non-volatile memory, a GPU, USB and HDMI ports, a LAN port, WiFi, and Bluetooth capability. It will also come with an installed operating system such as Windows 10 or 11. The mini-pc can do anything a laptop can while running the applications needed for complete control of mounts, cameras, focusers, dew heaters, etc. This includes running image capture software, guiding software, planetary software, plate solvers, planning software and imaging session automation and control software like NINA or SGP. For instance, on my mini-pc I have The Sky X for mount/camera/focuser control and image capture, Sharpcap for EAA, Ph.D2 for guiding, All Sky Plate Solver and ASTAP for plate solving, Cartes du Ciel as my planetary software, and Sky Tools 3 Pro for planning. I recently added NINA which will take responsibility for overall control and sequencing of my astro-imaging sessions which still uses TSX, Ph.D and ASTAP. In general, a mini-pc is not expected to do the heavy lifting of post processing the photos captured during an astrophotography session, although it is expected to handle the live image stacking, dark frame subtraction and stretching typical in an EAA session. Usually, the burden of post processing astro images is tasked to a separate, more powerful and more expensive laptop or desktop computer. But, there is no reason it cannot be done on the mini-pc if configured to do so which requires a keyboard, mouse and monitor. Even when post processing is left to a separate computer, it is imperative to have a keyboard, mouse and monitor to attach to the mini-pc for initial setup and for analysis in case something goes wrong. In two years I have only had to pull out these once in the field and it turned out that the problem was operator error, not something wrong with the mini-pc or my WiFi router. Still, having these as backup is essential in the rare case that something goes wrong.  My Beelink U57 with 5th Gen Core i5, 8GB RAM and 256GB SSD My Beelink U57 with 5th Gen Core i5, 8GB RAM and 256GB SSD Choosing a Mini-PC When it comes to mini-pcs there are a seemingly endless number of options available which constantly change as new hardware components become available. New mini-PCs can be found for under $200 on models with Celeron and Core i3 processers to over $1000 for models with high end processers, GPUs and lots of memory. Keep in mind that even with the same models, prices fluctuate frequently both up and down. The correct choice depends upon one's particular application, future plans and pocketbook. Typically, the trade off in performance and price leads to mini-pcs used for astronomy costing somewhere between $200 to $500. Beelink is probably one of the most popular mini-pc manufacturers in this price range. Recently, inexpensive models from Mele Quieter have gotten a lot of notice on the Cloudy Nights forum as well. Intel NUCs (Next Unit of Computing), designed and built by Intel, are also quite popular and include some of the high end mini-pcs as these NUCs come in many configurations including kits which can be customized to the users requirements.  When choosing a mini-pc the first feature to consider is the CPU. At this point in time mini-pcs used for astronomy usually include a Celeron or Core i3 processer for the less expensive models or an i5 processer for the slightly more expensive models. Many people report success in astrophotography and even EAA with mini-pcs using Celeron processors. However, for high data rate applications as is the case with larger format cameras (20Mpixels or larger) or live stacking of very short exposures (less than 5 sec subs) with dark frame subtraction and flat frame calibration for EAA, the Celeron class of processor may not be up to the more challenging tasks. In these situations an i5 processor would be a safer choice while the added cost of an i7 processer might be better applied to more RAM or a larger and faster SSD. For planetary imaging requiring extremely high image capture rates one should consider at least an i5 and possibly an i7 processor with fast SSD storage. Celeron processors found in these mini-pcs include the Gemini Lake J4125 and the Jasper Lake N5095. For Core i5 processers the Tiger Lake 113567 and Coffee Lake 8279U are typical. In addition to processing speed and cost another attribute of CPUs to be considered is the Thermal Design Power (TDP) which is indicative of the maximum power that the CPU can generate. The higher the TDP the more power one needs in the field to keep the mini-pc running all night long. One of the desirable features of the mini-pc is its lower total power consumption compared to a laptop. The accompanying table shows the tradeoff in CPU capability and TDP. After the CPU the amount and type of RAM and mass storage is probably the next most important consideration. 8GB of RAM is sufficient for most situations and is fairly common in pre-configured mini-pcs, while 16GB can help when many applications are open at the same time. As far as mass storage one should consider 128GB to be the minimum choice in which case you may have to constantly download image files to another storage device after an imaging session. I opted for 256GB which allows much more margin, but even then I sometimes wish that I had paid the extra for 512GB. The choice will depend on your imaging/EAA habit and how often you are willing to transfer images from your mini-pc to your processing pc. Mass storage on the mini-pcs often used for astronomy typically have one of three types of mass storage including M.2 SATA SSDs, M.2 NVE SSDs or eMMC. The first two can be replaced while eMMC is soldered onto the motherboard and cannot be replaced. NVE SSDs use the PCIe interface which is much faster than the SATA interface used by SATA or eMMC devices. All will work but the M.2 NVE SSD is the better choice for high data rate applications. Probably the next most important consideration in choosing a mini-pc is the number and type of USB ports because of the need to connect our many astro devices to the mini-pc. Most mini-pcs in the price range being discussed usually provide at least 4 USB ports in some combination of USB2.0 and USB3.0. Some also provide a USB Type C port with even faster data transfer rates. Don't forget to reserve one USB port for a WiFi dongle when using a wireless keypad and mouse. On other hand, if like me, you have a USB hub like the Pegasus Power Box which you use to connect your astro devices, you will only need to connect the hub to the mini-pc, preferably over a USB 3.2 port for fastest transfer rates. Another choice is whether or not to choose a mini-pc with a fan or not. Fans consume additional power. And they can, in principle, cause vibrations although I have never witnessed any such problem with my mini-pc attached to the leg of my tripod. On the other hand, fans will keep the CPU cool so that it can operate at its highest speed whereas air cooled mini-pcs can get hot causing the CPU to throttle back. Beelink tends to incorporate fans into their models while MeLE Quieter does not. Many folks agonize unnecessarily over the fact that some mini-pcs require 19V power input instead of 12V. This is easily rectified with an inexpensive DC-DC boost converter which takes a 12V input and provides a steady state 19V output. The boost converters are ~95% efficient while the AC transformer typically supplied with any mini-pc is likely ~80% efficient. I find the easiest way to incorporate these into my setup is to attach Anderson Power Poles to the leads and use Anderson Power Pole to 5.5 x 2.1mm adapter cables to connect to my equipment. All mini-pcs include an ethernet port for wired connection, WiFi and BT capability, along with one or more HDMI ports. You will need one HDMI port to connect a monitor initially to set up the mini-pc and any time something goes wrong with your connection to the mini-pc and you need to trouble shoot the situation. Mini-pcs come with Window 10 or Windows 11 software already installed. Look for the Pro version which is required for some remote connection software like Team Viewer and Remote Desktop.  Beelink SEI8 Beelink SEI8 Mini-PC Models to Consider Below are a number of different mini-pc models currently available. Prices will vary and over time models will change, but this can be a good starting point. Beelink has a large following in the astronomy community judging from posts on CN and is the brand I have used and been happy with for the past 2 years. You can search through all their models on the Beelink Amazon store. A few examples are worth considering. The Beelink U59 Pro comes with a Celeron N5105 processor, 8GB of RAM, a 500GB M.2 SATA SSD, 4 x USB 3.0 and 1 x USB C ports, 2 LAN ports, 2 x HDMI ports, WiFi, BT, and Windows 11 Pro. It has a cooling fan and operates on 12V and is currently on sale for $219. You can add 8GB more RAM for another $25. The Beelink SEi8 has an i5-8279U processor, 16GB of RAM, a 500GB M.2 NVME SSD, 4 x USB 3.0 and 1 x USB C ports, 1 LAN port, 2 x HDMI ports, WiFi, BT and Windows 11 Pro. It also has a cooling fan and operates on 19V and also has an auto startup feature so that you can set it to automatically turn on at a set time each day. This model is currently on sale for $397. Compared to the model above you get a faster processor, twice the RAM and a faster SSD.  MeLE Quieter 2Q MeLE Quieter 2Q If you are looking for a fanless mini-pcs, the models from MeLE Quieter are becoming popular among amateur astronomers lately. Here are two worth considering. The MeLE Quieter 2Q uses the Celeron J4125 processor, 8GB of RAM, 128GB of eMMC storage, a Micro SD card slot of storage expansion, 4 x USB 3.0 ports, 1 LAN port, 2 x HDMI ports, WiFi, BT and Windows 11 Pro. It does not have a cooling fan and can also be configured for auto startup. This model is currently on sale now for $210. Like most mini-pcs there are upgraded versions of this model with up to 512GB of eMMC storage for an additional $90. The MeLE PCG35 has a Celeron N5105 CPU, 8GB of RAM, a 256GB NVMe M.2 SSD, a Micro SD card slot of storage expansion, 2 x USB 2.0 and 2 x USB 3.0 ports, 1 LAN port, 2 x HDMI ports, WiFi, BT and Windows 11 Pro. It does not have a cooling fan and can also be configured for auto startup. This model is currently available for $310. Both of these MeLE models require 12V input power. Intel NUCs can be found at the Intel Store for as little as $200 to well over $1000. An example is the Intel NUC 10i3FNHN which currently lists for $499 and includes an i3-10110U processor, 8GB of RAM, an 512GB of PCIe SSD, 3 x USB 3.2 ports, 1 Thunderbolt (Type C) port, 1 HDMI port, 1 LAN port, BT, WiFi, an SD card slot and Windows 10Pro. It requires 19V for power.  GL.iNet Slate Portable Router GL.iNet Slate Portable Router Mini-PC Operation Being small and light, a mini-pc can be mounted on top of the telescope which minimizes the length of cable runs between cameras, focusers, dew heaters, filter wheels, the mount and the pc. Often the mini-pc can be found mounted to the leg of the tripod or at the base of the mount. If the mini-pc has a cooling fan, this may be the best place to mount it to minimize the chance of vibrations in the optical system. This is my typical configuration since I have a Software Bisque Mount with through the mount cabling. In addition to the mini-pc some method to connect between a laptop/tablet/phone and the mini-pc is required. This involves a remote desktop application like Team Viewer, VNC Connect, Remote Desktop or one of the many others which are free and easy to use. These generally require that the mini-pc has the Pro version of Windows to work. The second requirement for remote connection is the ability to make a WiFi connection. At home this could simply be your home internet network assuming that you have a LAN line to connect to the mini-pc in the back yard. I use a Cat5 cable I strung out to my backyard observatory 10 years ago to connect from my laptop anywhere inside the house to my mini-pc outside on my home network. In the field or at home if you don't have a wired connection in the back yard, you will need to create your own WiFi network. This is simple to do with an inexpensive portable router. I have reviewed 2 such inexpensive routers from GL.iNet in an earlier blog which you can find here. A video version of my review can also be found here. I have been using the GL.iNet 750S Ext (Slate) for 2 years and could not be happier. I can stay connected from inside my RV to my telescope up to 100 feet away. At home I can use the Slate as a repeater and connect to my home internet without the need for a LAN cable connection. GL.iNet has another model capable of higher data rates called the Beryl for just a few dollars more which is worth considering. If you need help setting one of these up, I created a video showing how to do this step by step. Summary Having used my mini-pc for two years both at home and at many star parties I have been extremely happy that I finally made the move to untether myself. With one exception (operator error) I have not lost any time due to problems connecting or using the mini-pc. And, I have not noticed any problems when using it for astrophotography or EAA. Hopefully I have given you a helpful overview of the considerations required to set up your own remote connection so that you can make the right choice for your situation. The one possible downside of using a mini-pc is that it tends to keep me inside, even at star parties, instead of out under the night sky. I have had to remind myself that one of the great things about being at a star party is to be able to look up and appreciate the wonder of the Milky Way with my naked eyes. So, I make it a point to spend some time outside both viewing the night sky and talking with my fellow amateur astronomers instead of spending the entire night away from the action inside the RV. You can find a complementary video tutorial on this subject on my YouTube channel which you can find here www.youtube.com/watch?v=TRk2wsrOnNM Beelink Mini PCs amzn.to/48Vp3Lm

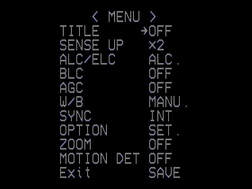

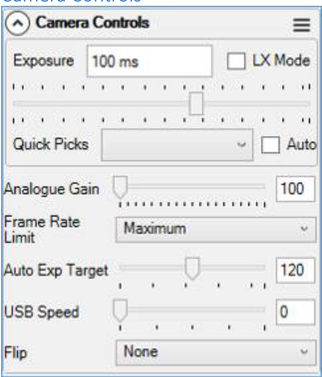

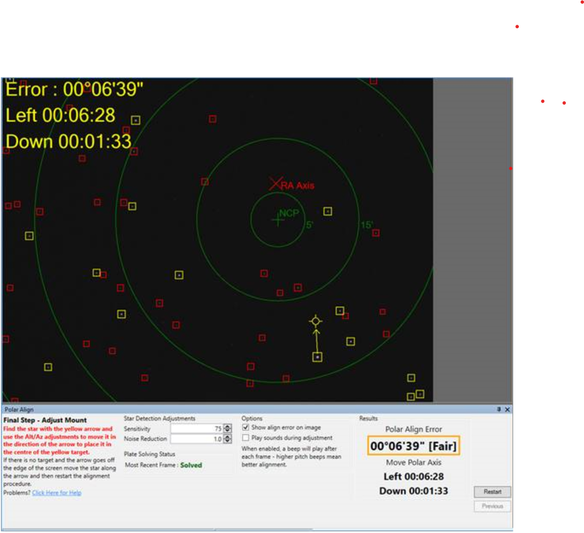

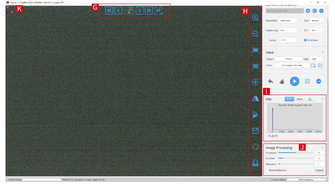

MeLe Quieter Mini PCs amzn.to/47KLXUK Intel NUCs amzn.to/47KM1ns GLi.Net Portable Routers amzn.to/4b1oamt Links are Amazon Affiliate links from which I can earn commissions at no cost to you. If you would like to support my web site and its content please consider using my links when ordering products.  Two years ago I decided that I was no longer willing to have my laptop tethered to my telescope with a long USB cable. When I am in the field I normally site inside my EZUp tent with my laptop to stay warm and to limit the light infringement on my neighbors. While this has worked well for many years, the cable presents a tripping hazard especially at star parties where other folks tend to stop by. And now that I have an RV I want to sit inside and not worry about running a USB cable through an open window or door. So, I looked into what is needed to go wireless and found that it was not at all difficult. First, we need computing power at the mount to run all of the software used to control the mount, camera, focuser, guider, dew heaters, etc. Second, some sort of WiFi either built into the computer or through a small travel router is required to link the computer at the mount to the device inside. Third, software designed to allow a laptop, tablet or phone to be connected to and control the computer at the mount is also needed. Let's look at each of these in detail. Off the Shelf Solutions There are a number of different ready made solutions available from the astronomy industry. On the high end there is TheSky Fusion (available from High Point Scientific) from Software Bisque. At the heart of the Fusion is a 64bit Hex-Core CPU with 4GB of RAM which drives TheSky imaging addition software which is included with the Fusion. A total of 190GB of on board memory is available to store images. It has an integrated WiFi with an external antenna to provide wireless connection to a pc, laptop, tablet or phone. It also comes with an ethernet port in case of the need for a hard wire connection and it has internal GPS. TheSky Fusion integrates USB hub capability with 4 USB3.0 ports and can operate as a power distribution hub with 8 configurable power ports capable of supplying up to 40A using Anderson Power Pole connectors for reliable connections. At 4.2lbs the Fusion is designed to be mounted on top of the telescope to allow for simpler cable management. With a price of $1895 TheSky Fusion is on the high end of off the shelf WiFi solutions but it is certainly packed with useful features combining the functions of a computer, WiFi, USB hub and power distribution all in one. Another high end solution comes from Prima Luce Labs in their line of four different telescope control units ranging in price from $795 to $2195. The least expensive model is the Eagle LE (available from High Point Scientific) while the most expensive model is the Eagle 4 Pro (available from High Point Scientific) The LE has an Intel Celeron Dual Core CPU with 4GB of RAM and 120GB SS memory while the Pro has a Quad Core I5 CPU with 16GB of RAM and 480GB of SS memory. Both provide connectivity via WiFi with an external antenna and through an ethernet port. Both models have ample USB ports and 7 power ports, 3 of which allow voltages to be configured from 0V up to 12V. The Pro model includes a GPS. Any software can be installed onto these units just like a normal pc and, like the Fusion, these units are designed to be installed on top of a telescope. The Eagles use proprietary connectors on the 4 12V non-configurable power ports so one has to add the cost of these cables to the total cost of the unit. Like TheSky Fusion Prima Luce Labs' models combine multiple capabilities into one device. ZWO's ASIAIR Plus (available from High Point Scientific)is a much less expensive WiFi solution but with less computing power and fewer bells and whistles. At the heart of the Plus is a Raspberry PI 4 processor with 32GB of internal storage and a slot for a MicroSD card. It has an external WiFi antenna and an ethernet port. Unlike the models from SB and Prima Luce Labs, the ASIAIR will only work with ZWO cameras, focusers and filter wheels but it will work with a large variety of mounts. Like the SB and PL units it also acts as a USB hub with 4 USB ports and a power distribution hub with 4 12V power ports capable of a total of 5A. The ASIAIR is also designed to be mounted on top of a telescope but has a much smaller footprint than the SB and PL units and weighs less than 0.5lbs. At a price tag of $299 the ASIR Plus is a slimmed down version both in size and capability of the more expensive SB and PL models. The Stellarmate Plus is the least expensive ready made WiFi solution at $229. Like the ASIAIR it uses a Raspberry PI 4 processor, has 2GB of RAM and includes a 32GB MicroSD card for storage. In addition to the WiFi the Stellarmate also has an ethernet port but no external WiFi antenna. It has 4 USB ports but no external power ports. Like the ASIAIR the Stellarmate is compact and light weight. Unlike the ASIAIR, Stellarmate works with a wide variety of astronomy equipment. It includes a copy of EKOS Astrophotography software and is compatible with a variety of other software applications.  GL.iNet AR750S Portable WiFi Router GL.iNet AR750S Portable WiFi Router Build Your Own Solution While the above ready made wireless solutions will work, each has its cons. The high end models are expensive and better CPUs, and more RAM and memory can be found for less money. The lower cost models only come with a Raspberry PI processor, which works, but is limited in ultimate capability and they have very little RAM and memory. With just a little bit of effort, and not much more cost, if at all, compared to the ASIAIR and Stellarmate options, one can put together a better custom tailored solution on their own. I chose to build my own solution with the features and capabilities that I wanted. A custom WiFi solution requires three components. The first is a CPU at the mount to run all of the software used to control the mount, camera, focuser, guider, dew heaters, etc. This could be an inexpensive laptop, a headless Intel NUC or mini-pc, or a home brew Raspberry PI. I decided that the best solution for me was a headless mini-pc because it offered the best price to feature ratio. I bought a Beelink U57 mini pc with an Intel Core I5 processer, 8GB RAM and a 256GB solid state drive for under $360. And considering that I use a Pegasus Power Box Advanced which cost $330 I have all of the features that TheSky Fusion offers that I need for less than half the price. The mini pc comes with Windows 10 Pro installed so that I can run any of the typical software that I use such as The SkyX for mount/camera/focuser/guider control and image capture. I can also use SharpCap if I want to do electronically assisted astronomy (EAA), PhD for guiding, Nina or Sequence Generator Pro for image sequencing, etc. I am also not constrained to work with any one manufacturer's equipment as a mini pc works with any mount, camera and accessory that is ASCOM compatible. While my model is no longer available, you can find something similar for just $249 or choose from a wide variety of mini-pcs from Beelink with different processors, RAM, memory, USB ports, etc. While my mini-pc uses 12V, most mini-pcs or Intel NUCs require 19V which can easily be supplied using a 12V battery and a 12V to 19V DC-DC voltage converter like this one. The second component is WiFi. I found two inexpensive portable wireless routers from GL.iNet that I bought and tested, the GL-MT300N (Mango) and the GL-AR750S (Slate) models. The 750S provided greater range due to its pair of fold up antennas and also offered 5GHz capability which helps to mitigate potential interference on the 2.4GHz band from nearby equipment. I am able to set up inside my RV up to 100 feet away from the mini-pc and maintain a good connection all night long with the Slate. I can also set up just inside my house and stay connected to the mini-pc inside my backyard observatory when at home. You can read my review of the Slate and its smaller Mango alternative in my Feb '21 Blog or view my video review of these two on YouTube. There is a newer model with fold up antennas, the GL-MT1300 (Beryl), which offers twice the data rate of the Slate. The last component to make this all work is a way to make the remote connection from the laptop (or tablet or phone) to the mini-pc to use the laptop as a terminal to view and control the software on the mini-pc. There are many free remote connection options and I tried two of them, Remote Desktop and Team Viewer. I chose Team Viewer but any of the many options will work fine. The choice seems to come down to personal preference. Also, you will most likely need to have the Pro Version of Windows software installed in order to use the remote connection software, but most of the mini-pcs seem to come with that.  Router - Mini PC - PPBA On Tripod Leg Router - Mini PC - PPBA On Tripod Leg Set Up & Operation I choose to have my mini-pc attached to the leg of my telescope tripod since my SB MyT mount can supply all the power I need to the cameras and focuser through the mount itself. I also have through the mount wiring for the dew heater. For some people this will work, but others may choose to set up the mini-pc or Intel NUC on the telescope itself. These are small enough and light weight enough as to add little inertia to the telescope. The Slate router gets its power from the mini-pc. Power to everything comes from a LiFePO4 battery or Jackery solar generator which is fed through the Pegasus Power Box Advanced. I just power up the PPBA, turn on the mini-pc and the mount and step away to my laptop. It takes a few minutes for the router to set up its WiFi signal which I connect to with my laptop. Once connected to the router I run Team Viewer to connect to the mini-pc and begin my session with The SkyX and any other software that I need which resides on the mini-pc. Images are captured difrectly to the mini-pc and retrieved later for post processing on my laptop. When my session is over, I simply park the mount, turn off the cameras and close The SkyX and any other software (ShapCap, PhD) that I have running on my mini-pc. Then I turn off the mini-pc remotely. I can leave everything like this or I can go over to the telescope and disconnect the battery or turn off the Jackery. Additional Considerations If you go the route of a headless mini-pc or NUC I suggest that you carry with you a mouse, keypad and small LCD display. This way, if something goes wrong you can connect to the mini-pc and see what is going on. You can use a wired mouse and keypad you may already have lying around or you can purchase a wireless set similar to the one I did. You will also need a small LCD display and there are many to choose from. It is also worth knowing that the wireless routers I discussed above can also work as WiFi repeaters at home which is how I use mine. The router can be set up to connect to the home WiFi and then I can use my laptop from anywhere inside my house to connect to the mini-pc out in the observatory. Of course, how well this works depends upon the strength and coverage of your home WiFi signal, but it is a nice additional advantage of the wireless router if you do not already have either WiFi or cable at your backyard observing location. Summary For those who prefer ready made solutions there are several very good options which we discussed to choose from across a broad range of prices and features. However, if you are inclined to set up your own system you can customize it to your specific needs, including only those elements that you need and avoid paying for features you do not want. And, a custom solution will give you the greatest flexibility in terms of equipment and software compatibility. You can find a companion video I made on this topic here www.youtube.com/watch?v=quoWbvN5VWc&t=1220s Some links are Affiliate links where I can earn with purchases at no cost to the buyer which help to support this web site. If you would like to support my web site and its content please consider using my links when ordering products.  Celestron 6SE with ASI224MC Celestron 6SE with ASI224MC Why SCTs In this installment of my "EAA for Beginners series" we will discuss the use of a Schmidt Cassegrain Telescope (SCT) for EAA on an Alt-Az mount. SCTs seem to be a popular choices for EAA for good reasons. First, large apertures up to 14" are possible with an SCT because the cost per inch of aperture is so much less than that of a refractor. Second, because the SCT design uses folded optics, SCTs are more compact than the same size aperture Newtonian. With its smaller moment of inertia for the same weight Newtonian, an SCT places less demands on the mount for smooth tracking and is guides better in the wind. But the versatility in focal ratio (or focal length) may be the biggest reason SCTs are popular for EAA. An SCT is natively f/10 but can easily be reduced to f/6.3 for an non-Edge model or f/7 for an Edge model with the addition of a focal reducer. And, with hyperstar capable models, focal ratios of f/1.9 to f/2.2 are achievable depending upon the model SCT. As I discussed in detail in an earlier installment of this series, the lower focal ratio results in a faster optical system so that much shorter exposures are needed providing spectacular images in real time and less demands on telescope tracking. This versatility is like having 3 different telescopes in one with just the added cost of the focal reducer and hyperstar. Any size SCT which can be found in sizes from 5" to 16" primarily from Celestron and Meade will work for EAA . I have used 6", 9.25", 11" and 14" SCTs myself for EAA with great success and you can find some real time images in the "My Images" section of this web site. The tradeoffs with a larger size scope is cost and the need for a larger and more expensive mount. That is why some consider an 8" SCT as a ideal size scope in terms of aperture vs size and weight.  Celestron Single Fork SE Alt-Az Mount Celestron Single Fork SE Alt-Az Mount Alt-Az Mounts Just as SCTs are very popular for EAA, Alt-Az mounts are also popular. Alt-Az (Altitude-Azimuth) mounts do not track the rotation of the earth like Equatorial (EQ) mounts do. EQ mounts have two axes of rotation called Right Ascension (RA) and Declination (Dec). EQ mounts must be polar aligned so that the RA axis, also called the Polar Axis, follows the earth's axis of rotation. This is done with a procedure called Polar Alignment (PA) in which the elevation of the mount is set to the local latitude while the Polar Axis is carefully aligned with the north celestial pole. By doing this the mount rotates about its RA axis so that it matches the earth rotation to keep objects centered in the field of view (FOV). This allows for long exposures of up to many minutes determined by the quality of the mount and the precision of the PA. While an Alt-Az mount also has two axes of rotation and motors on each axis to find and track objects in the night sky, it cannot exactly match the earths rotation. The Azimuth axis is defined by the local horizon and the Altitude simply by the height of an object in the sky. There is no latitude adjustment knob to account for the tilt of the earth's axis. Only at the north and south poles will the Azimuth axis of an Alt-Az mount be pointed at the celestial pole and the mount be able to track the earth's rotation. Everywhere else on the surface of the earth, an Alt-Az mount can keep a star centered in the field of view, but it cannot prevent the surrounding stars in the FOV from appearing to rotate around the central star. This field rotation can cause objectionable elongation in the appearance of stars in images depending upon how long of an image exposure and where in the sky the object is located. The typical rule of thumb is that exposures must be limited to less than 30seconds unless the object being viewed is nearly due east or due west to avoid star trailing or elongation. The actual details are much more complicated and can be found on this web site here. Despite this, Alt-Az mounts work very well for EAA since the trend in recent years has been to take short exposures, much less than 30seconds, and use software like SharpCap to stack successive image frames in real time to give images with an effective exposure of minutes of longer without star trailing. Despite its limitation in following the earths rotation, Alt-Az mounts have several advantages for EAA compared to EQ mounts. First, Alt-Az mounts are less expensive than their EQ counterparts. Also, Alt-Az mounts are typically lighter than EQ mounts for the same load capacity which makes them easier to transport, whether from inside the house to the back yard or to a distant dark site. Finally, since an Alt-Az mount cannot be Polar Aligned, it is much easier and faster to set up a telescope on an Alt-Az mount and get started viewing objects in the night sky. Alt-Az SCTs The combination of SCTs on Alt-Az mounts are now very popular for EAA and come in a number of different sizes and configurations. These are some of the least expensive telescope setups for SCTs. You can get a Celestron Nexstar 5SE SCT (available from High Point Scientific, Agena Astro or Amazon) on an Alt-Az mount for $936, while the Celestron Nexstar 6SE (High Point Scientific or Agena Astro or Amazon) is only slightly ore expensive at $1099 and the Nexstar 8SE (High Point Scientific or Agena Astro or Amazon) is $1600 as of this writing. Celestron also offers a better mount in its Nexstar Evolution series (High Point Scientific, Agena Astro) which is available with a 6" SCT for $1679, an 8" SCT for $2199 and a 9.25" SCT for $2849. The Evolution mount offers integrated WiFi so that the scope can be controlled wirelessly from a phone or tablet, it includes an internal rechargeable Li battery which should last all night long, has improved gears for better tracking and other improvements like manual clutches, etc. The larger the aperture the greater the magnification of the image, but also the more the telescope weighs. The field of view (FOV) of a 6" SCT is 2.46X larger than the FOV of a 9.25" SCT at the same f-ratio so more of very large objects like M33 can be viewed in the smaller SCT, but more detail will be seen in smaller objects like M82 with the 9.25" SCT. The weight difference between an 6" SCT and an 8" SCT is small with the former weighing just 10lbs and the later 12.5lbs. But, at 20lbs the 9.25" SCT weighs twice that of the 6". On the other hand the Evolution mount/tripod weights only 33% more at 28lbs compared to the SE mount/tripod at 21lbs. The SCTs discussed above are Celestron's standard optical tubes. They also make their Edge series of optical tubes (High Point Scientific, Agena Astro) which have additional optical elements in the baffle tube which is designed to give a flatter FOV so that stars are more pin point from center to edge. These are offered in 8" and larger OTAs and come at a premium price with the 8" Edge OTA costing ~$300 more than the non-Edge version and the 9.25" version costing ~$1500 more. If you objective is to also do traditional astrophotography you should seriously consider an Edge version OTA. On the other hand, if you only plan to do EAA the added expense of an Edge OTA is not so clearly justified. Celestron does not offer an SE or Evolution mount with an optical tube larger than 9.25" because the weight of the larger OTAs is too great for these single arm mounts. If you want a larger OTA on an Alt-Az mount you must choose a dual arm fork mount like Celestron's CPC series (High Point Scientific, Agena Astro) with 8" to 11" OTAs. With dual arms these telescopes come with built in GPS, improved drive gears, a heavy duty mount, an auto-guider port, clutches and Periodic Error Correction (PEC) capability. The dual fork telescopes come at much higher cost with the CPC8 at $2600 compared to $2199 for the 8" Evolution. But an even bigger difference is found in the weights, exacerbated by the fact that the OTA is permanently attached to the mount in this design. The CPC8 mount/OTA is 42lbs while the tripod is 19lbs. This compares to 12.5lbs for the 8" OTA and 28lbs for the Evolution mount which makes the SE and Evolution designs much easier to transport and set up compared to the CPC design. Meade does not offer single fork SCTs but they do offer dual fork versions. They only offer these in their ACF (Advanced Coma Free) version of optical tube similar to the Celestron Edge. The 8" ACF sells for $3000 and comes with built in GPS, and over-sized mirror, PEC, and more. Meade offers versions all the way up to OTAs of 16".  Celestron 6.3X SCT Focal Reducer Celestron 6.3X SCT Focal Reducer Focal Reduction with SCTs As I mentioned in the beginning, the ability to use SCTs at multiple focal ratios is what makes them so versatile and ideal for EAA. Natively SCTs are f/10 which results in very high magnification, especially with cameras using a small chip. For instance, an 8" SCT at f/10 has a focal length of 2000mm. When used with the low cost ASI224MC camera which has a chip diagonal of 6.1mm the magnification is approximately 2000/6.1 = 328. Such high magnification not only means that only the smallest DSOs will fit in the field of view, but that it can be very hard and frustrating to locate the object to begin with. In addition, the exposure times needed to see detail may need to be very long. For these reasons, EAA is most commonly performed at focal ratios of f/2 to f/7 to obtain a combination of wide field and fast optics. Focal reduction is fairly straightforward requiring that a focal reducer be placed between the telescope and the camera. To obtain the specified focal reduction ratio the camera must be placed at the correct distance from the back of the focal reducer according to the manufacturer's specification, usually within a couple of millimeters. If the camera is too close, the focal reduction will be less and if it is too far, the focal reduction will be more. Also, if the spacing is off by too much it may result in vignetting and other types of image distortions. Adapters are available to achieve the correct spacing and spacers in various sizes can be used to fine tune the spacing. For instance, Celestron has a series of T Adapters designed for each of their different OTAs including Edge and non-Edge designs.  Celestron's Edge Series T-Adapter Celestron's Edge Series T-Adapter There are many focal reducers on the market but not all are designed to work with SCTs. Celestron offers a 0.63X focal reducer (High Point Scientific, Agena Astro or Amazon) for their standard OTAs and a 0.7X reducer for the Edge OTAs (High Point Scientific , Agena Astro) to reduce the focal ratio down to f/6.3 and f/7 respectively. You can also get the Starizona Night Owl reducer for 0.4X reduction ) or the Optec 0.33X focal reducer (High Point Scientific) to produce an even lower focal ratio of f/3.3. All of these are both focal reducers and field flatteners which improves the sharpness of the stars from the center to the edge of the FOV. Since EAA is not meant to produce the high quality images sought by astrophotographers, one can even use a generic 0.5X focal reducer (High Point Scientific, Agena Astro, or Amazon) to get down to a focal ratio of f/5. These come in both 1.25" and 2" versions and are much cheaper than the focal reducers from Celestron, Starizona and Optec. If one is not terribly concerned about vignetting it is also possible to stack focal reducers to achieve an additional focal reduction such as stacking two 0.63X reducers to get a focal ratio of ~f/4. HyperStar While the HyperStar adapter(High Point Scientific) is a field flattener and not actually a focal reducer, it does enable the Celestron SCT focal ratio to be reduced from f/10 to ~f/2. The Hyperstar is a compound set of lenses which replaces the secondary mirror on the front of the OTA. Just unscrew and remove the secondary mirror and screw the HyperStar in its place. The camera is then screwed into the back of the HyperStar adapter so it is looking directly at the primary mirror which has a focal ratio of between f/1.9 to f/2.2 depending upon the aperture of the OTA. Camera cables such as the USB cable for camera control and image capture along with a power cable if camera cooling is used are routed from the front of the OTA to the back. They typically do not cause much interference in the image. Many older model OTAs are not compatible with the HyperStar attachment so check before you buy. Also, be careful not to overtighten the HyperStar onto the corrector plate as it can become frozen in place as it did on my C14 requiring removal of the corrector plate to get the HyperStar adapter off. Hyperstar speeds up the optical system dramatically with required exposures reduced by the square of the ratio of the native and HyperStar focal ratios, or (10/2)^2 = 25 times. The effect is dramatic. In addition the reduction in focal ratio greatly increases the FOV by a factor of 10/2 = 5 which makes HyperStar great for viewing very large DSOs like M33, the North American Nebula, etc. Summary